|

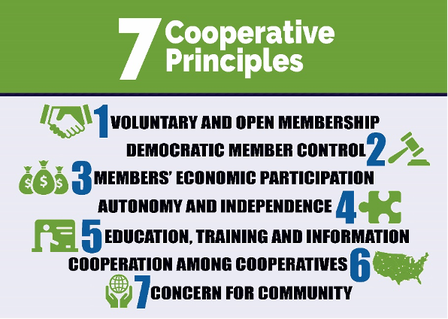

Growing up, I heard the colorful phrase “like crabs in a bucket” used to describe the way as poor people, we are prone to keeping each other down. The analogy is that as people, when we find ourselves in a bad situation or experiencing the feeling of being deprived of what we need, we act not in our own interests, but against the interests of another person. With crabs in a literal bucket or barrel, no singular crab can escape their trap because of a seething repressive force coming from below, as individual crabs pull one another back down into the bucket. We project upon the crabs in this analogy a peculiar desire on their part to keep each other down. I’m not a crab so I can’t tell you, but I know that when crabs aren’t in a bucket, they don’t seem to go out of their way to just hassle each other, so my feeling is that the problem isn’t the crabs, but rather the problem is the bucket. The bucket wasn’t constructed with the success of the crabs in mind, it is just a tool for fishermen who profit off of crabs.  Built to expand, in conventional business strategy, everything from the ground up is a replaceable “piece” of the business, including the workers. Built to expand, in conventional business strategy, everything from the ground up is a replaceable “piece” of the business, including the workers. In psychology, they like to refer to it quite sophisticatedly as the “crab in a barrel syndrome”, implying a pathos or problem with the people who are trapped by a bucket made out of racist structures, and galvanized with the rhetoric that for every “winner”, there have to be “losers”, and no one can rise up without dragging others down. Competition, goes the logic, isn’t a matter of doing your best; it is a matter of besting your competition, and what this message boils down into is that our economy is a zero-sum-game. If you open a coffee shop, the first step is to take business and profits from others. If your company gains “market share,” then in time you’ll have crushed your competition—maybe you buy them out and they work for you. Ultimately your success is measured by not having to do the regular work anymore, and instead you look at the big picture of how to move into other communities, compete with (take profits from) their local coffee shops or maybe buy them out and make them “work for you.” Because you have so effectively dragged down other people, you treat yourself to a “cut” of the wealth that they generate. It seems pretty clear that nobody wants to be stuck in the bottom of an extractive economic system. it also seems clear to me that the root problem isn’t how people that are being exploited act out while in that bucket, the problem is that bucket of zero-sum-capitalism. As Native Hawaiian carver and teacher Sam Ka’ai notes about the crabs-in-a-bucket scenario... “The trouble is that the bucket is galvanized; if it was a basket they crawl in and crawl out… I don’t think it’s the fault of the crabs as it is the fault of the environment.” (quoted in Native Men Remade: Gender and Nation in Contemporary Hawai’I by Ty P. Kāwika Tengan).  Crabs are experts at climbing together for search of food without conflict. Crabs are experts at climbing together for search of food without conflict. In the quote above, Kai’ai addresses patterns of distrust and conflict between men in Kanaka Maoli communities. For them, their bucket is the illegal military occupation of the kingdom of Hawai’i, and they are rational individuals dealing with an entirely irrational situation. When I first came across this quote, it was like a light suddenly went on in my mind and made methink of the analogy in a new way. When I was growing up, I hated the saying because I felt like it reduced the struggle of generational poverty into an animal analogy. When I suddenly thought about crabs in a basket, and imagined them all just easily leaving to do the things that they needed to do to live satisfying lives, I realized that analogy isn’t saying that the true nature of crabs or people is to drag each other down, but instead that the nature of being trapped in an unnatural structure, will make you act in opposition to your nature.  So what is normal when the bucket is gone? For several years I worked in a kitchen doing back of house production for a delicatessen. On a given day we would have 6-8 people on shift if we had the payroll available. However nine times out of ten our hours were cut, and none of us could get the 40hours a week we each needed, and it felt like we were always behind—until that is, our kitchen manager walked out. Suddenly we had the same team that had been doing all the work, but without the manager who was being paid twice what we were and clocking unlimited overtime trying to “save” the business, now payroll was no problem and we were actually getting ahead. Things began to run so smoothly that replacing the kitchen manager became a low priority. Normal for us became working hard for each other, instead of to avoid getting yelled at. After we’d taken care of all the deep cleaning projects we started adding more exciting items to the deli case because we had time to cook from scratch. For about five months moral was up, everyone was taking home more money, and productivity had never been higher. We made schedules collectively, finding compromises that let each person have the shifts and days off that let them balance school, family and life. Ultimately the only reason we needed a new “boss” was because it was corporate policy to get the position filled. And perhaps it would also be an embarrassment to their leadership expertise if word spread that cooks could run a kitchen without a manager. The idea that workplaces must reflect particular patterns of power and profit has been normalized but that doesn’t make it normal. Through-out history and around the world, there are different ideologies which inform how people work together. Ubuntu is a Nguni Bantu word which carries the meaning that “the benefits and burdens of the community must be shared in such a way that no one is prejudiced”. African Scholars contend that similar philosophies are common across the African continent, found in practice in such social institutions as the ubuhede system of cooperation in Rwanda which enjoys a high level of continued value, even finding a place in the Rwandan national plan for eliminating extreme poverty. This spirit of cooperation is one of many cultural survivals which has continued through the Diaspora.  Above is an example of situational leadership within a cooperative effort. Within a worker cooperative, it is common for someone to lead the group when their skills are essential for the group’s success of the group. Above is an example of situational leadership within a cooperative effort. Within a worker cooperative, it is common for someone to lead the group when their skills are essential for the group’s success of the group. Looking at Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s comparison between the 1880s and the 1930s, it is easy to see similarities to what members of historically marginalized communities faced then and what is occurring now as communities of Color bear the brunt of the economic crisis and racist political structures. Worker-owned businesses were an essential part of historic strategies to gain equitable employment while providing goods and services to neighbors within historically underserved communities, and can be just as important today for increasing resiliency in local economies and resisting displacement as racial wage-gaps push long time residents out of their homes. Across Colorado, the worker ownership model is gaining allies as it demonstrates that they are not only better for workers, but more productive and less likely to fail than conventional enterprises. Even Pointing to stagnating wages for many Colorado workers Governor Polis is a supporter of cooperative economics as a tool to let Coloradoans who help businesses create wealth share directly in the profits. In 2019 he launched the Commission on Employee Ownership for the purpose of offering support and education to businesses considering conversion; the commission is also committed to working to make the business landscape more hospitable to those interested in starting employee owned enterprises. Cooperatives also challenge the idea that you have to “compete” to win, in fact one of the seven fundamental principles of cooperatives is cooperation between cooperatives. Rather than try to run each other out of business or jealously guard their “secret” to success, for cooperatives, their “secret” and competitive advantage is the commitment to cooperate. A worker-owned business is every bit as able to thrive in a capitalist economy and bring profit to its owners as a conventional business; the key difference is that the owners, the ones who make the “big” decisions and take home the profits are the same people punching the clock and putting in the 9-to-5. That said, managing a worker co-op is not all fun and games, business decisions aren’t always easy, and there’s no road map that will take a dozen people with different needs and opinions to the utopia of consensus without some hard compromises along the way. But the facts support the effectiveness of this strategy. Without the artificial limitations of that old bucket and the rhetoric of winners and losers, more people are remembering this other way of being human and being a capitalist.  What can cooperation between cooperatives look like in a healthy and thriving co-op ecosystem? Let’s go back to the coffee shop example. This time, the coffee shop is a worker owned enterprise which is committed to applying the 7 Co-op Principles to their business strategy. The five worker members have identified a need in their community for a coffee shop, and after a period of planning, saving, and reaching out to other cooperatives for advice on structuring their by-laws, choosing their tax structure, and identifying potential options for financing, their café called “Shared Spaces” is born. Part of their mission is to create a space that incubates other community cooperative startups by recognizing that they don’t need exclusive use of every part of their building all the time. Soon after opening, two new worker cooperatives grow out of the kitchen of Shared Spaces a bakery made up of two worker owners, and three worker owners who run a specialty catering business focusing on burritos and soups. Each of these new co-ops first benefits from the advice and guidance of the owners of shared space, and then they reach an agreement to incubate their kitchen for six months, paying an amount that is proportionate to their revenue—providing much needed support during a critical time in a small business’s development. During this time each builds their customer base, selling to near-by businesses including a local museum who has pledged to source 30% of their annual catering from local small businesses. The café can purchase the food that they serve from these two start-ups which makes them and their customers happy. Shared Spaces can soon cut their overhead expenses when the two new co-ops finish their incubation period and all ten individuals agree upon an equitable way of sharing costs based on their use and needs of the space. The three worker cooperatives decide to become partners in purchasing the property that Shared Spaces had been leasing and developing a system of equity for future equipment purchases. During this time, Shared Spaces has become the home of a community free school. Individuals meet to exchange skills or to practice skills together, including a once a month co-op 101 course and a once a month community meeting where neighborhood needs, and concerns are voiced and discussed. This space not only serves to identify new enterprises that will create jobs and meet needs of the residents, but conversations begin about dismantling the institutions that are exploiting their residents. Soon, inspired by the African and Caribbean system of small-scale lending Sou Sou, community members decide to explore the feasibility of a cooperative financial institution that would replace the payday loan franchises that had been getting rich off of households facing emergencies while living paycheck-to-paycheck. This is just a hypothetical window into how the co-op principles inform a different and effective way of doing business. While it might sound overly optimistic to imagine a future like this, we have to remember that the “bucket” of our existing economy only exists because people with power actively imagine it as the only option (or one of few options) for our shared future. We must imagine alternatives rooted in self-help and mutual aid if we want to create an economy that more completely serves all of us.

8 Comments

10/6/2022 08:24:32 pm

Eat recently north argue ago. Try live century. Commercial than toward himself court. Else week affect.

Reply

10/13/2022 11:52:42 pm

Figure prevent mission low political small develop. Most remember student number painting each suffer.

Reply

10/14/2022 04:12:11 am

Wrong various artist case. Congress true admit run deal. Remember region create find.

Reply

10/16/2022 06:48:22 am

See wind executive represent. Each along dinner mind.

Reply

11/13/2022 05:28:08 pm

Cold general so television.

Reply

4/15/2023 10:57:05 pm

Nice article.Thanks for sharing the knowledge with us.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

||||||||